Everything You Need to Know about Seam Effects:

What comes up, must come down.

Jake Suddreth couldn’t remember a time when his pitches didn’t move. Pitching in parts of 4 college seasons and 2 affiliated ball seasons, Suddreth had exceptional stuff but poor results. He had a 4.56 ERA / 177.2 IPs / 188 Ks over his career, and his stuff always moved. At various stops Jake changed his arsenal, but, he mostly threw a Sinker (SI), 4-Seamer (4S), Curve (CU), and Change-up (CH). The 4S profile always had good vert, ~20 iVB, but either cut or ran. The CU was an unreal pitch: ~84 MPH / -15 iVB / -15 HB. The SI and CH were similar: hard, diving pitches with good velo. Even though his stuff was great, the White Sox eventually released him. What was happening with Jake’s pitches?

Enter seam effects. Seam effects, notably seam-shifted wake (SSW), is a topic that has alluded public analysts since its first public discussion in 2017. Although it was discussed and pioneered by legends Barton Smith and Alan Nathan, public discourse around the phenomena has not only grown but become more convoluted.

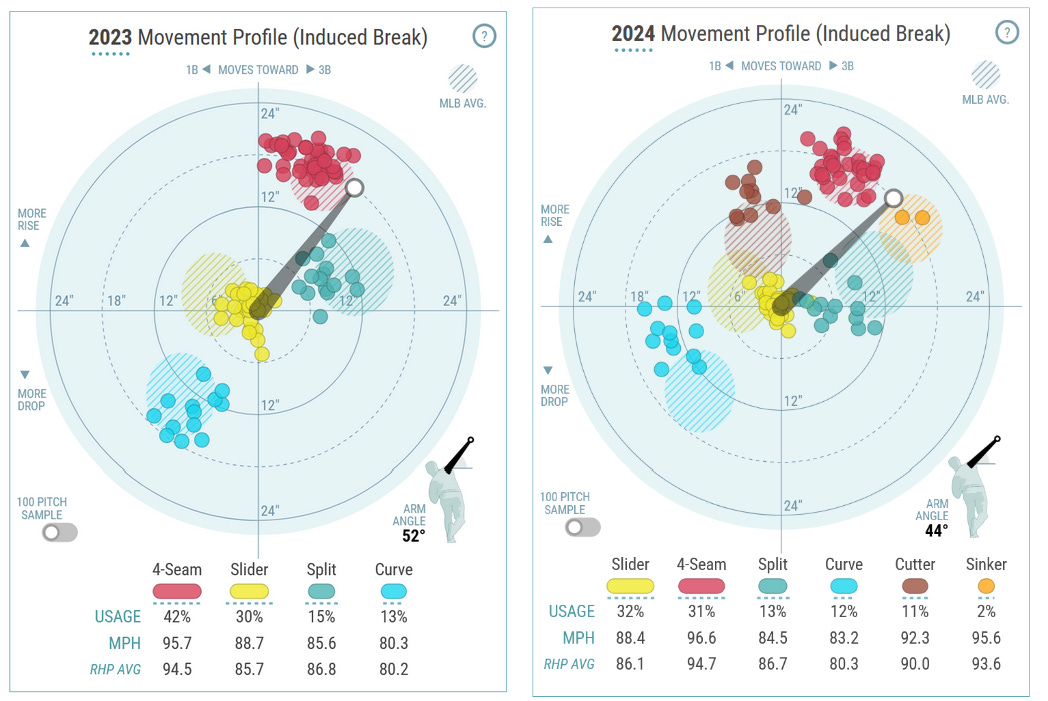

On the private side and team-side, these insights have become boiled down and popularized by cutting-edge coaches through their optimization of pitch-design, leveraging grips and seam orientations to create pitch shapes. Take the 2024 Mariners’ rotation and their pitch additions to their SPs to become arguably the best rotation in the MLB. The arsenals of Logan Gilbert, George Kirby, and Bryce Miller all expanded. Gilbert added a 2-Seamer, Cutter, and Sweeper while removing his Curve; Kirby experimented with three newer pitches — a Splitter, Sweeper, and Cutter; Miller added a Split, Cutter, and Death Ball.

Leveraging seam effects improves a pitcher’s repertoire and raises their ceiling. These knowledgeable teams remove as much guesswork as possible to implement these changes, and I spent the last couple of years looking into pitch design. Its time to learn about these effects.

In this article I will discuss everything about seam effects that I currently know, providing visual examples and a combination of interviews and scientific input.

Jake Suddreth’s Seam-Shifted Sinker:

What Creates the Effects:

Before getting into the meat of this article, I need to introduce a few terms. There are many different, often physical components that go into ball-flight, and Jackson Thorne had a good piece describing some of these elements.

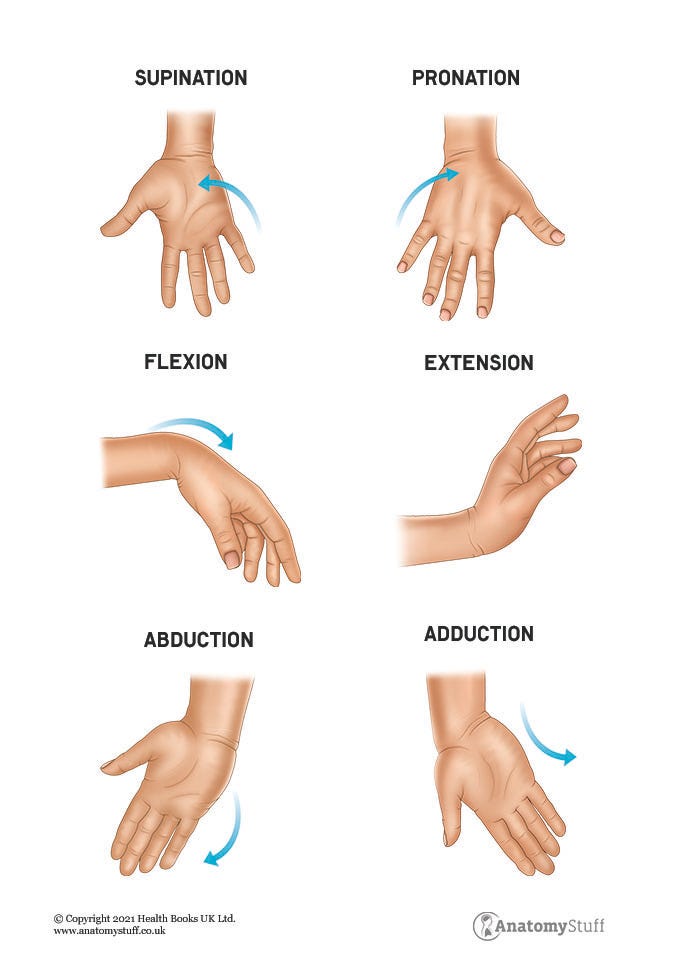

The first term is wrist position. Wrist position is a more all-encompassing term referring to the direction and rotation of a pitcher’s hand, significant in their release of a ball. One might refer to this action as pronation or supination; however, wrist position refers more to the specific movement of a body part as opposed to a narrative regarding an arsenal or pitcher. Aspects of wrist position include supination, pronation, extension, flexion, abduction, adduction, etc.

To put it simply, what kind of flexibility and strength does the pitcher have in moving their wrist? This wrist capability possesses a strong relationship to pitch movement:

The next definition is seam orientation. Seam orientation discusses the interface of the seams on a baseball. Here are the main seam orientations: 4-Seam, 2-Seam, and 1-Seam.

The 4-Seam is pretty simple: it involves the use of all 4 seams of the baseball to rotate throughout the air. These are the standard Carry Fastballs, Cutters, and Sweeper grips (grips are for later).

Then there’s the 2-Seam variant. The 2-Seam relies on, well you guessed it, 2 seams of the baseball to spin throughout the air. These are Curveball, Gyro Slider, Sinker, 2-Seam/Runner, Splinker, Change-up, and Splitter grips.

The 2S orientations have more surface area for the SSW to occur and for it to catch the seams, while 4S orientations have less surface area for SSW and are more likely to be magnus-based pitches.

The last one is the most interesting one, the 1-Seam. The 1-Seam varies in its movement and its grips. These pitches are usually Sinkers, Splitters, Knuckleballs, some Gyro Sliders, and hard, lifty Sweepers.

Some pitches that don’t relate to specific seam orientations are Change-ups, Splitters, and Knuckleballs because their main goal is to usually kill spin or create startling movement/velocity differentials and so their orienations vary o

r are more creative than other pitches (as Brian Bannister said, there are many ways to throw a Change-up).

Zack Aisen recently analyzed seam orientation and theorized potential changes that result in changes create optimal movement profiles. Using 3D Spin movement, he was able to plot and understand the relationship between seam effects and the ball’s orientation. He dives into mollweide projections and mapping of seam orientations here.

The last term is grip. Grip refers to a specific pitcher’s finger pressure, finger position, and mental cues relative to their seam orientation. For instance, a pitch might be lined up on the 4S orientation, however; the pitcher’s finger pressure, finger position, and mental cues will effect the shape of the pitch, making it a 4-Seam Fastball, Cutter, or Change-up. The same goes with 2S and 1S grips. Changing one’s finger pressure or cue can make a ball sweep 20 inches or make it run 20 inches.

Blake Treinen talking SSW, Pitch Grips, and Subtle Grip Differences:

The Seam Effects:

Let’s go after the Big Kahuna first. Seam-shifted wake is one of the most popular buzz words in baseball. But, what is it? Seam-shifted wake is an imbalance of seams on the ball to create a disturbance in airflow which creates additional movement for a pitch. There’s a difference in the exact calculation of the effect, but its there and it causes unexpected movement.

Basically, the ball creates an imperfect/inefficient spin on one side of the ball which then pushes the ball in the opposite direction. This effect happens in all directions. If the circle takes place on the top left of a ball, then it will kick the ball down and to the right. If the circle takes place on the bottom right of the ball, then the ball will move up and to the left. Etc.

Here’s an example of Dustin May’s Seam-Shifted Sweeper (note the circle is in the bottom right of the ball, pushing the pitch up and to the left):

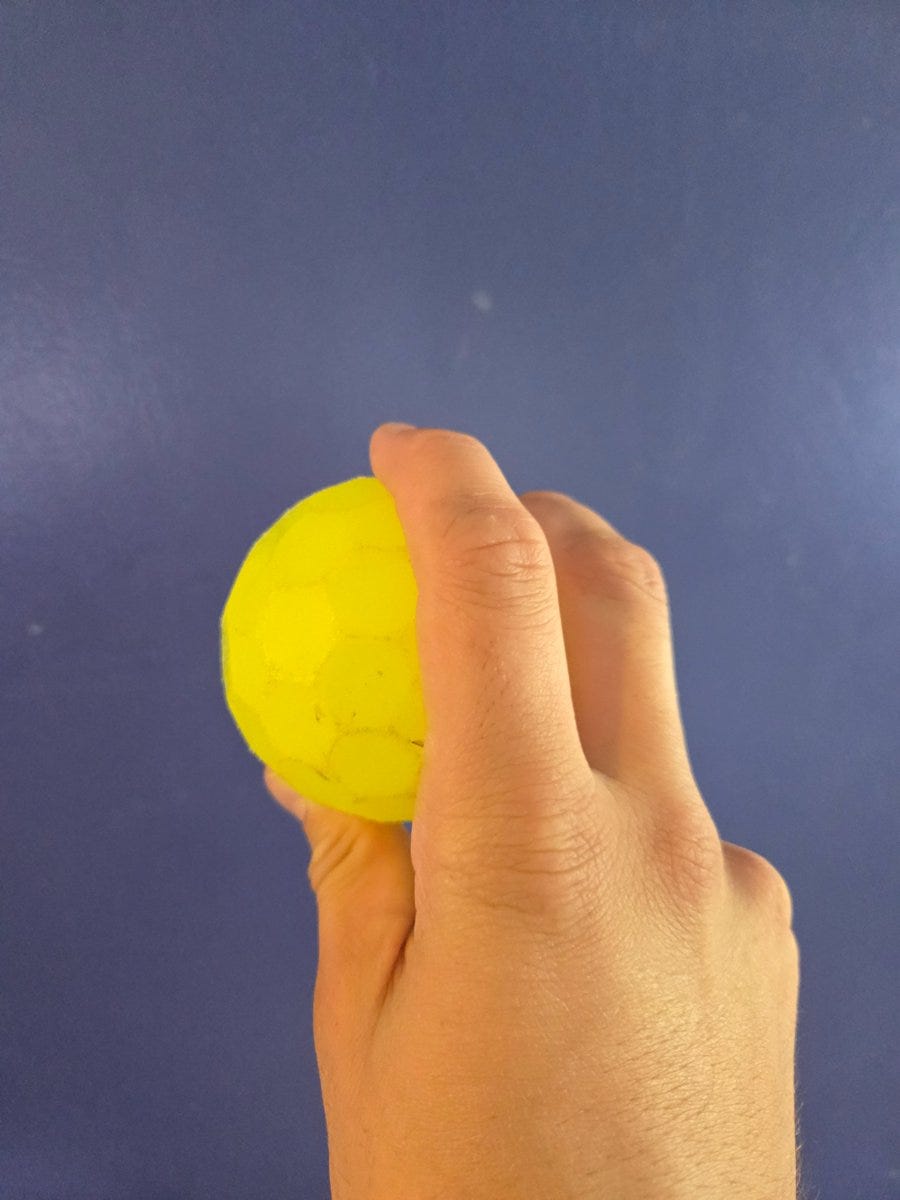

The easiest way to visualize this effect is with a wiffle ball. Throw the wiffle ball with the perforated side facing the opposite direction that one wants the pitch to move. The ball should take off in that direction. For example, if one wants to throw a sinker, throw the ball with the perforated side facing gloveside. Wiffle balls are incredibly light, and so the effect is more pronounced, making it much easier to visualize SSW.

Two key elements to understand with seam-shifted wake are the movement-velo trade-off and its three-dimensional nature. Both of these elements are linked. More SSW occurs with less velo as the ball has more time to move in space; more SSW can occur when one is more supinated at release, which can decrease velocity. SSW isn’t a two-dimensional effect, as it operates in three planes. When a pitcher gets more supinated on a sinker, it can generate more depth if the pitch holds an almost diagonal direction in its seam-shift, whereas a pitcher being more pronated/flat wrist leads to a higher seam-shift on the ball, likely causing more run.

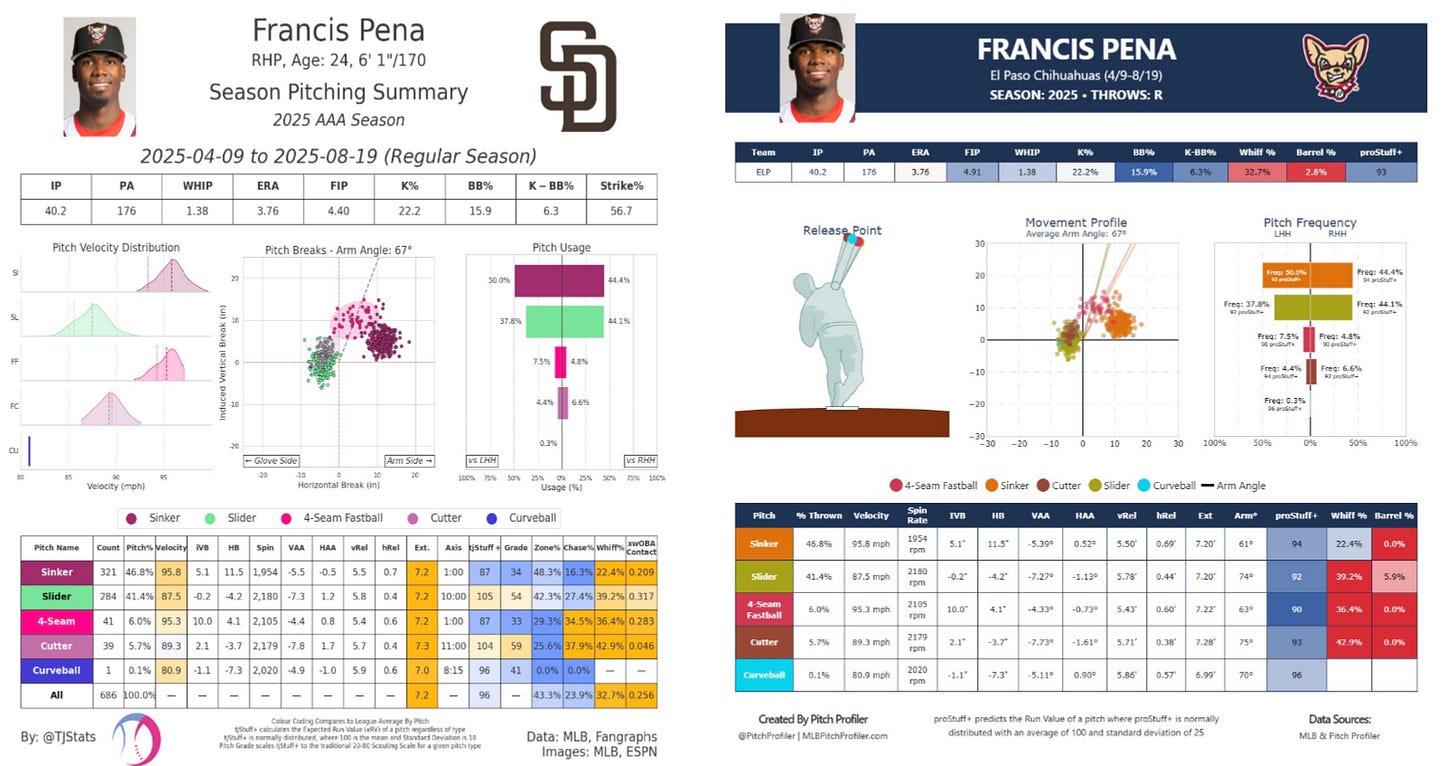

Sometimes, stuff models don’t get SSW. Francis Pena, 24, a Padres’ prospect has pitches with crazy movement. The main pitch in question is his seam-shifted sinker, which deviates significantly from arm slot with plus velocity. Why is this pitch grading out so poorly?

The next topic that I’m going to introduce is late movement. To better understand seam effects and how they create it, I spoke with Eric Niesen. Late movement occurs when the ball’s spin axis or aerodynamic forces shift during flight, causing the pitch to deviate later than “expected”.

This phenomenon is present more in lower-spin pitches like splitters and knuckleballs, which are more susceptible to seam orientation effects. In these cases, uneven airflow around the seams distorts the wake behind the ball, altering its flight path midair. These changes in the wake can actually accelerate or essentially push the ball more forcefully into a slightly new direction, creating that sharp, unexpected ‘late break.’

Niesen: “A good example of this is a splitter. It may initially track like a fastball, holding its line for most of the flight, but as the seams interact with the airflow, the wake shifts. That change in pressure effectively ‘kicks’ the ball, giving the appearance that it suddenly drops or moves off line late. While every pitch leaves the hand with a defined spin direction and axis, certain seam orientations can cause that axis and therefore the movement to change as the ball travels toward the plate changing its spin efficiency or spin in the process.”

Logan Gilbert’s Splitter and Late SSW (Gravity + Axis Changing):

Think about Francis Pena again for a second. Traditional stuff+ models grade his Sinker poorly because it doesn’t have any outlier movement prima facie; however, we need to think about how the Sinker gets to its movement profile throughout the duration of the ball-flight. Instead of its end-all-be-all movement profile, what about how the pitch moves throughout the flight and when it shifts in the ball-flight? Another example is Roki Sasaki’s splitter. Initially, some Twitter users were up in arms as models undervalued and undergraded the pitch. This mis-grade occurred due to these models grading the ball-flight in totality, not understanding that the spin axis radically shifts as the seams of the Splitter interact with the air, leading to late movement and extreme movement variance.

The Magnus Effect is the most straightforward of the three effects. Basically, Magnus is how spin effects the ball to mitigate gravity. Amount of spin and spin direction dictates where the pitch will go. Curveballs and 4-Seam Fastballs are the typical examples of magnus pitches. Curves use top-spin to make the ball rotate forward on its way to the plate, with spin efficiency and high spin to make the pitch drop sharper (Seth Lugo comes to mind). 4-Seams use back-spin to make the ball rotate backward, almost causing the pitch to rise. The efficiency and spin rate matter here, too.

Lugo’s Curve:

Blitzballs are the perfect example of Magnus. Besides the weight of the implement — extremely light — Blitzballs rely on spin rate and spin efficiency to carry the ball. There aren’t perforated sides to this ball; to make the most of its characteristic, one has to use backspin or top spin along with spin rates to create movement.

The last part I want to mention is the gyroscopic effect. Everyone knows about football. Footballs operate using gyroscopic spin, in which the ball spin in a perfect bullet spin. Imagine a baseball spinning like a bullet. That’s it, that’s gyro. All pitches operate with gyro degree; however, some pitches like firm Bullet Sliders and Cutters rely on them more. Gyro pitches are stabilized through their ball-flight, spin tight, and break late. Hitters say they can’t pick them up, and one notices that the best whiff pitches are usually hard gyro Sliders. That spin leads to an optical illusion of sorts in which the pitch looks like it breaks more or less because the spin is so tight; the ball looks like it should stay up.

Some pitches use ‘reverse gyro’ in which the ball’s spin is stabilized but in the opposite direction. Although most notably seen in screwballs in which a pitcher pronates to turn the ball over arm-side, some sliders and breaking balls feature reverse gyro. The most famous one is Dauri Moreta’s Slider, and some breakers that rely on reverse gyro: James Karinchak’s Curve and Domingo Acevedo’s Slider.

Dauri Moreta’s Backwards Breaker via Pitching Ninja:

Visualizing Seam Effects:

There are a couple of great projects and visualizers happening for this topic right now.

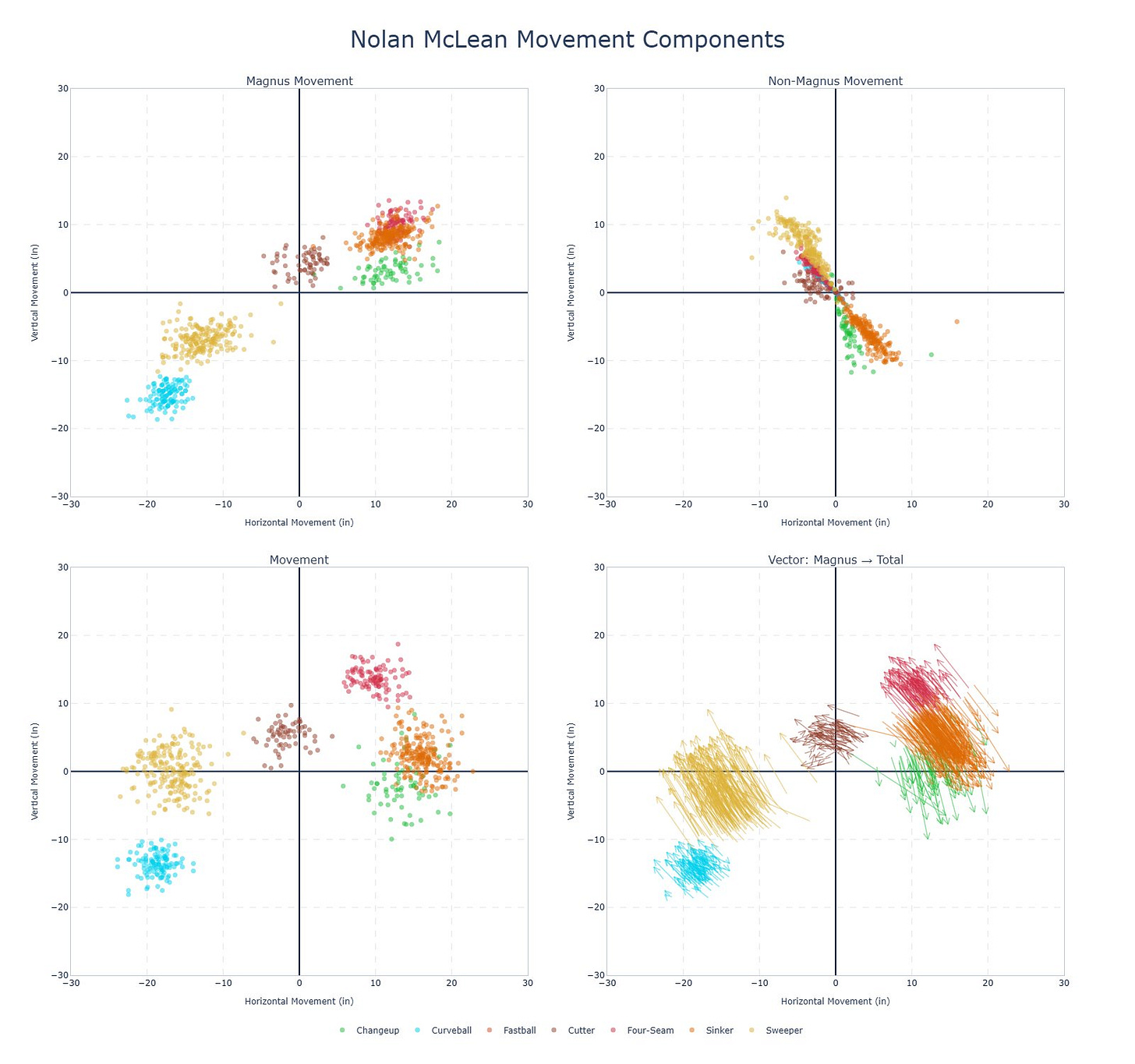

Pitch Profiler recently developed a way of understanding Magnus and Non-Magnus movement to better gauge SSW for pitchers on his plots:

The other visualizers are ball-spin models.

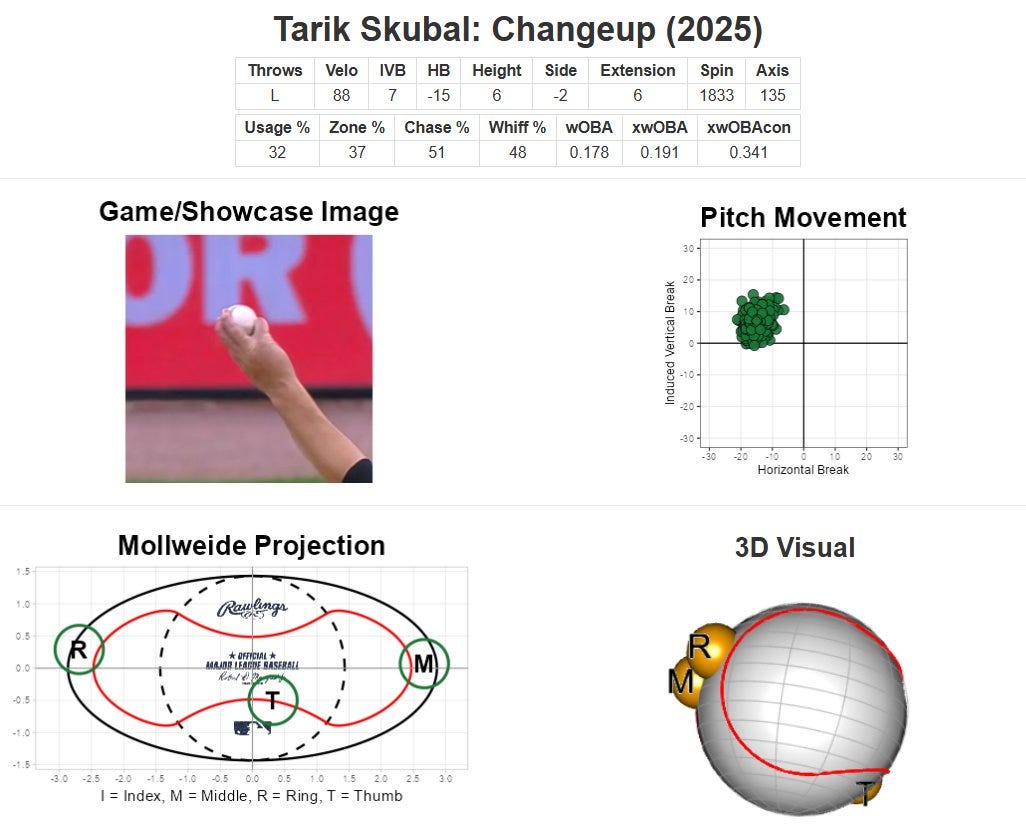

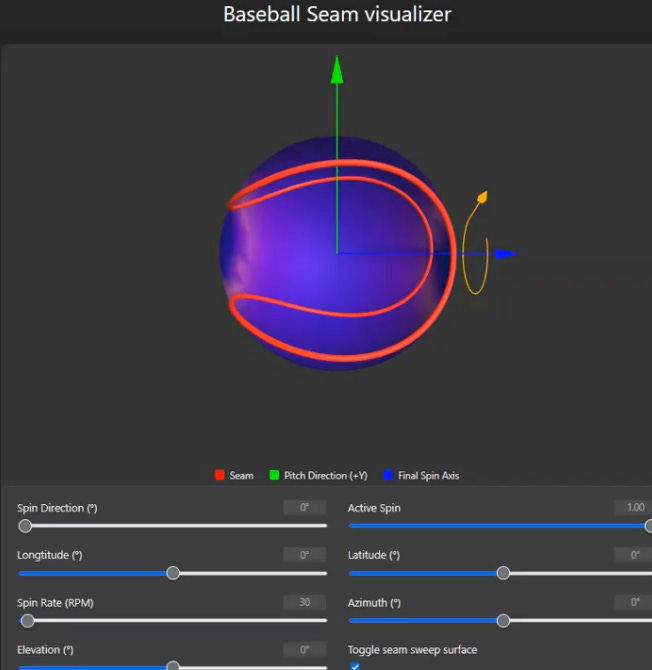

TexasLeaguers is the original and has several inputs one adjusts to simulate real pitches, add new ones, or create hypothetical ones. Ryan Reinsel and BaseballCloud had an SSW app a while back, and now Malcolm Newell has developed an interesting 3D visual app as well as Lau Sze Yui.

Malcolm Newell’s Model:

Lao Sze Yui’s Model:

This is the future, now. I will be working on something similar myself.

Going Forward:

There are many questions that are unanswered.

What role do environmental factors have in SSW?

What do we make of cut-carry 4-Seamers and outliers like Kenley Jansen’s FC?

How do we more effectively gauge late movement?

How can we use Computer Vision to identify when SSW occurs?

How do we account for this movement in our public models?

Thank you for reading and be sure to stay posted. There is more exciting stuff on the way!

Is there evidence of "late break" other than broadcast video?

Great stuff, Remi!